Tools: The Bash Agent: Notes from Testing SLMs on Linux

Source: Dev.to

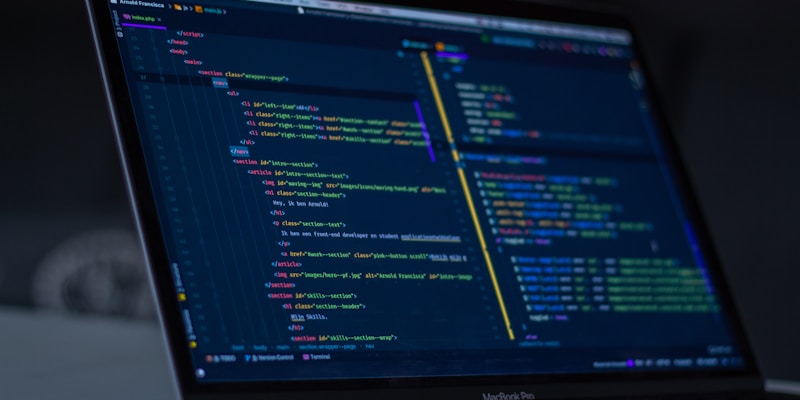

I’m not a software developer. I’m a retired engineering technician currently interested in testing slms or small language models. I do this in CPU-only mode and always on a Linux OS. Much of this testing happens in the same type of environments that pro devs deploy to: Linux servers, containers, CI runners, and Unix-style shells. Using this particular setup and testing the gemma-3-4b slm, has led me to a simple observation: within the operating system, many of the tasks I was asking the small language model to help with are already solved—efficiently and deterministically—by the OS itself and its powerful shell - Bash (or bash-like shells such as zsh). This isn’t an argument against AI - I'm an advocate of AI. And it’s not a claim that Bash is “smarter” than a model in any general sense. Bash can’t reason, plan, or operate outside the operating system boundary. But inside that boundary—files, logs, processes, streams—it is a remarkably capable agent. A typical AI-driven workflow for something like log inspection involves loading large files into memory, tokenizing them, running inference, and interpreting probabilistic output. On my CPU-only system, this routinely pegs cores at full utilization - something I don't want to do for long stretches. The same task, expressed as a simple shell pipeline, completes almost instantly and barely registers on the machine. From a testing perspective, this matters. When an slm is busy doing a job that the shell can do instead - counting errors, matching patterns, or enumerating files, it’s consuming resources without exercising what makes it valuable. These cycles can be reserved for tasks that actually benefit from language, synthesis, or judgment. In practice, I see this pattern most often not as a deliberate replacement of tools like grep or awk, but as a byproduct of modern “agent” setups. Raw system artifacts are handed to a model first, with the OS invoked later—or not at all. It’s understandable, especially when everything already lives inside a Python or agent framework, but it sends basic system tasks through a layer meant for interpretation rather than execution. For tasks within the Linux runtime, Unix tools remain unmatched at what they were designed to do. Pipes compose cleanly. Behavior is explicit. Output can be easily inspected. There’s no ambiguity and no inference cost. I've learned, at least for my use cases, that the most productive role for language models in these environments isn’t execution, but assistance. I've been working and learning with Linux for 15 years and it's a lifelong pursuit. So, an slm (or llm) that can explain unfamiliar flags, suggest a pipeline, or translate intent into a shell command is genuinely useful to me. A model that tries to BE the pipeline is much less so. Linux already provides a rich set of primitives for system state - ie - inspecting and manipulating files, processes, and streams. When testing models, I’ve found it helpful to let the OS do that kind of work, and to judge the performance of the models I’m testing with problems that require interpretation rather than mechanics. This division has made my testing clearer, faster, and easier on my hardware. Sometimes, especially on Linux, that shell’s all the “agent” you need. Ben Santora - January 2026 Templates let you quickly answer FAQs or store snippets for re-use. Are you sure you want to hide this comment? It will become hidden in your post, but will still be visible via the comment's permalink. Hide child comments as well For further actions, you may consider blocking this person and/or reporting abuse